The Expedition of Malaspina-Bustamante: 1789-1794

The Expedition of Malaspina-Bustamante: 1789-1794

Malaspina marked a before and after in this type of overseas expeditions

In September 1788, Navy Lieutenant Alejandro Malaspina, together with his friend José de Bustamante y Guerra, proposed to the Spanish government the organization of an expedition, which was later called the Malaspina expedition. It was a political-scientific excursion around the world, in order to visit almost all Spanish possessions in America and Asia.

This journey was made known by the promoters as "Scientific and recreational journey around the world" (1788); during the journey it was known popular and publicly as "Expedition back to the world." On arrival at the Court in 1794, as it did not return through the Indian Ocean and the Cape of Good Hope as a result of the late war between Spain and France, it was called "Ultramarine Expedition started on July 30, 1789"; and when the work of the expedition (in 1885) was first published by the ship's lieutenant Pedro Novo, it was made known as "Political-Scientific Journey around the world by the Uncovered and Atrevida corbites, under the command of the ship's Captains Don Alejandro Malaspina and José Bustdon and later known in 1794."

At present, several Spanish institutions have launched a large scientific expedition of circumnavigation that is named after this sailor in recognition of his contribution: the Malaspina expedition (2010- 2011)

The intense exploration of the Pacific by France and England at the end of the 18th century led to the reaction of the Kingdom of Spain. Since the Magallanes expedition crossed the Pacific and discovered the Philippines, Spain had considered the South Sea to be its exclusive property, controlling the Philippines in the west and almost all of its eastern shore, from Chile to California. But the interference of other nations was not the main reason for this expedition. It was essentially the scientific character of French and English explorations that caused a response from Spanish intellectuals. It was evident the desire to emulate the journeys of Cook and La Perouse through an ocean that for two and a half centuries was considered a Spanish sea. British historian Felipe Fernández- Armeto points out that:

The [Spanish] monarchy of the time devoted an incomparably higher budget to scientific development than to other European nations. The New World empire was a vast laboratory for experimentation and an immense source of samples. Charles III loved everything about science and technology, from watchmaking to archaeology, from aerostatic balloons to forestry. In the last four decades of the 18th century, an amazing number of scientific expeditions went through the Spanish empire. Botanical Expeditions to Nueva Granada, Mexico, Peru and Chile gathering a complete sample of American flora. The most ambitious of those expeditions was a trip to America and across the Pacific by a Spanish subject of Neapolitan origin, Alejandro Malaspina.

The Uncovered Corbites and the Atrevida

The purposes of the expedition would be to increase knowledge of natural sciences (botany, zoology, geology), to make astronomical observations and "build hydrographic charts for the most remote regions of America. "The project was approved by Charles III, two exact months before his death. The expedition, which had the corbettesAtrevidaandDiscoveredhe left Cadiz on 30 July 1789, carrying on board the flower and cream of the astronomers and hydrographs of the Spanish Navy, such as Juan Gutiérrez de la Concha, also accompanied by great naturalists and cartoonists, such as the painting professor José del Pozo, the painters José Guío and Fernando Brambila, the cartoonist and chronist Tomás de Suria, the botanist Luis Née, the naturalists Antonio Pineda and Tadeo Haenke (the quality of the crew did not reduce to their scientific endowment: he also participated in the heroic expedition, which he was also involved in the "Alcaligar,"). The ships were specially designed and built for the trip and were baptized by Malaspina in honor of James Cook's shipsResolutionandDiscovery(Atrevida and Discovered).

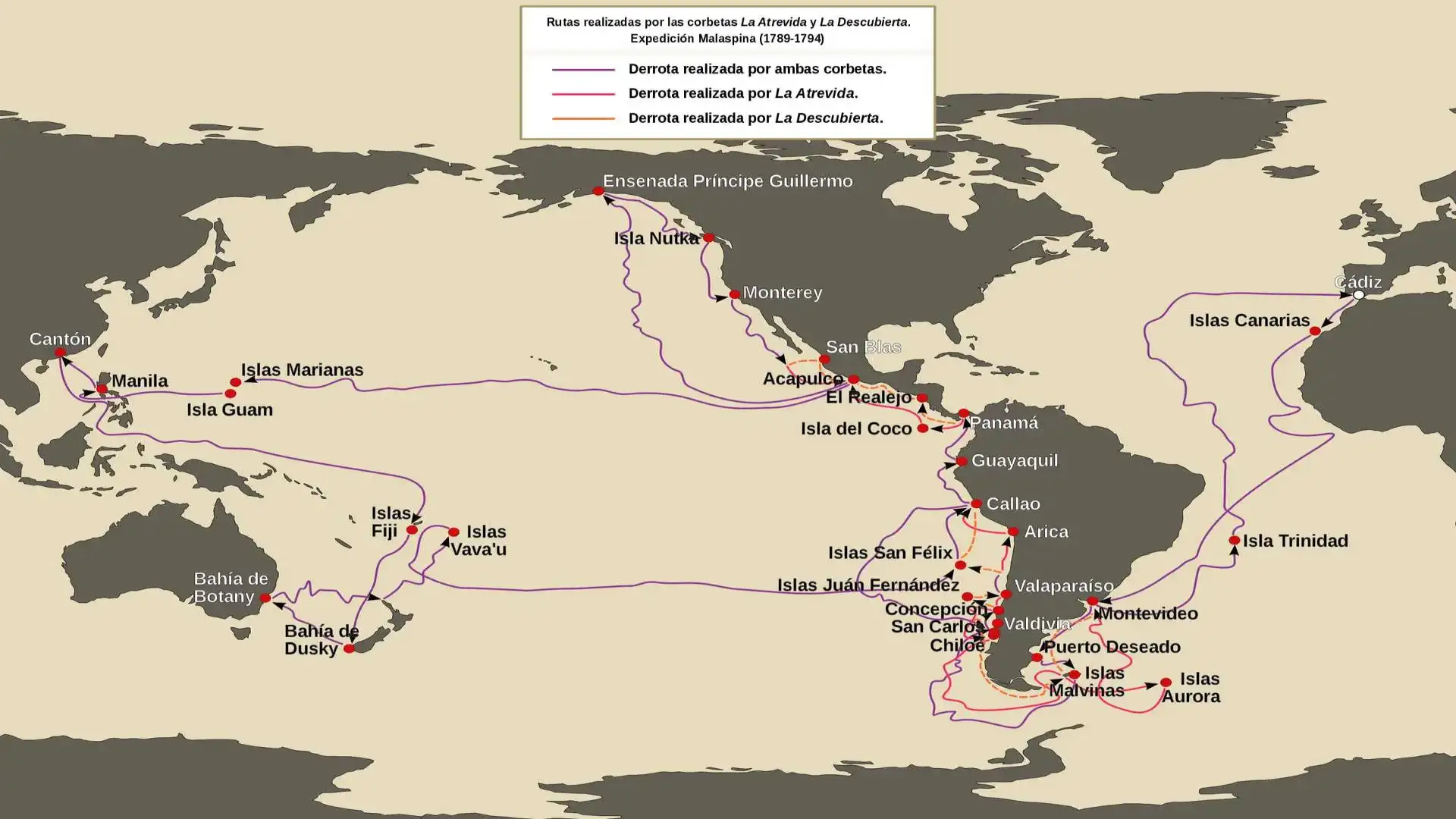

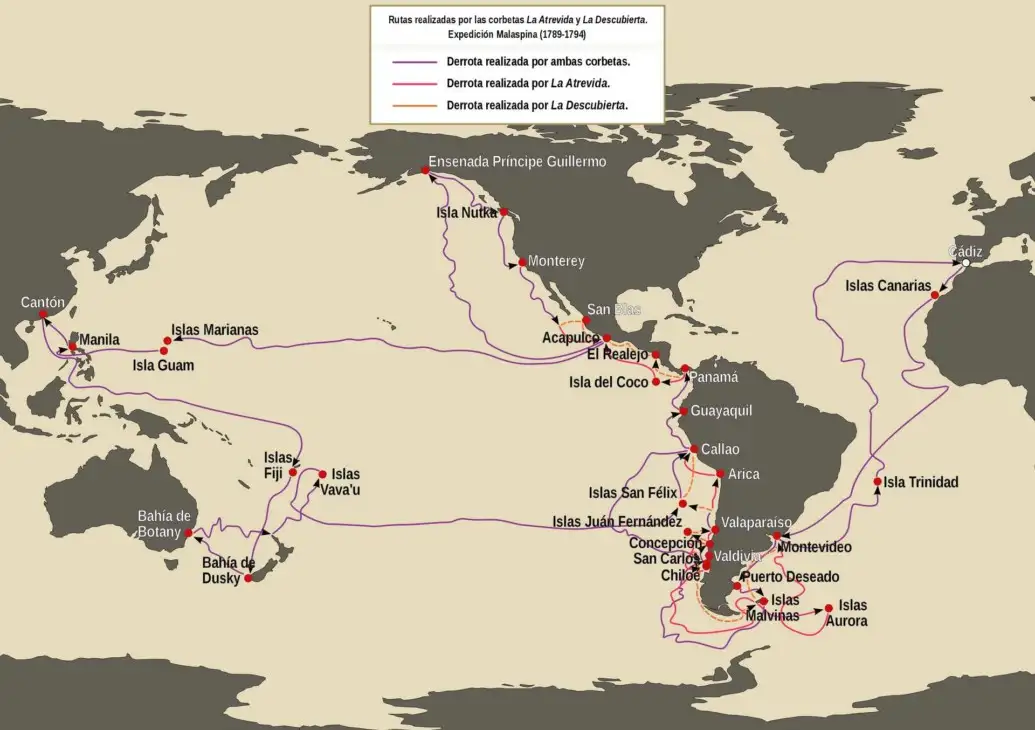

After a few days on the Canary Islands, they sailed along the coast of South America to the Rio de la Plata, arriving in Montevideo on September 20. From there, they went on to the Malvinas Islands, stressing earlier in Patagonia. They bowed the Cape Horn and passed to the Pacific (13 November), exploring the coast and highlighting on the island of Chiloé, Talcahuano, Valparaiso, Santiago de Chile, El Callao, Guayaquil and Panama, to finally reach Acapulco in April 1791.

The Expedition off the coast of Acapulco, in 1791

When they arrived there, they were commissioned by King Charles IV to find the Northwest Pass, which was supposed to unite the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Malaspina, instead of visiting Hawaii as he intended, followed the king's orders, reaching Yakutat Bay and Fjord Prince William (Alaska), where they convinced themselves that there was no such step. He returned south to Acapulco (where he arrived on October 19, 1791), after having passed the Spanish post of Nutka (on Vancouver Island) and Monterrey in California.

In Acapulco, the Viceroy of New Spain ordered Malaspina to recognize and map the Strait of Juan de Fuca, south of Nutka. Malaspina requested two small ships, the Subtle and the Mexican, putting them under the command of two of their officers, Alcalá Galiano and Cayetano Valdés. These ships left the expedition and went to the Strait of Juan de Fuca to comply with the order.

The rest of the expedition went to the Pacific, then sailing through the Marshall Islands and the Marianas and founding in Manila, Philippines, in March 1792. There, the corbites were separated. While the Attrevida went to Macau, the Discover explored the Philippine coast. In Manila, the botanist Antonio Pineda would die for a few fevers. Reunited, in November 1792, both corbites left the Philippines and sailed through the Célebes and Molucas Islands, then heading to the South Island of New Zealand (25 February 1793), mapping the Doubtful Sound fjord.

The next scale was the British colony of Sydney, from where they returned to the port of El Callao, playing on the island of Vava'u, and from there, by the end of Hornos, again grounding on the Malvinas Islands. At the beginning of 1794 the Corbeta Atrevida, a member of the expedition, was commanded by the ship captain José de Bustamante and Guerra, separated from his twin ship in the Malvinas Islands and went to verify the discoveries of the South Antilles as well as those of the San Pedro Islands (now better known as South Georgias). The Atrevida recognized the exact coordinates of the Aurora Islands: it saw the main of the Cormoran on 20 February of that year, then watching all the other islands including the Black rocks; they returned to Cadiz on 21 September 1794. The expedition collected maps, composed mineral and flora catalogues and carried out other scientific research. But it did not simply address issues of geography or natural history. On each scale, the members of the expedition made immediate contact with local and potential scientific authorities to expand the research tasks.

The Atrevida corbeta sailing between the icebergs

On his return to Spain, Malaspina presented a report, Political-Scientific Journey around the world (1794), which included a confidential political report, with critical political observations about the Spanish colonial institutions and favourable to the granting of a wide autonomy to the American and Pacific colonies, which was worth it that, in November 1795, he was accused by Manuel Godoy of revolutionary and conspirator and sentenced to ten years in prison in the castle of San Antón de La Coruña.

The goal of Malaspina and Bustamante was really ambitious. They aspired to draw a reasoned and coherent picture of the domains of the Spanish monarchy. For this, he not only had the work of his collaborators, but also investigated the materials of the main archives and funds of Spanish America. Through their newspapers and writings, they took place the different aspects of the reality of the empire, from mining and the medicinal virtues of plants to culture, and from the population of Patagonia to Filipino trade. In this way it culminates, following the principles of the Enlightenment, the discovery and scientific experience of three centuries of knowledge of the New World and the Hispanic tradition of geographical relations and questionnaires of Indias. And they do it under a formula characteristic of the period, so, imbued by the scientific and naturalist creed of the Enlightenment, what Malaspina actually did was to compose a true physics of the Monarchy.

On their return, the Malaspina and Bustamante expedition had accumulated an enormous amount of material: the collection of botanical and mineral species, as well as scientific observations (they came to draw seventy new nautical charts) and drawings, sketches, sketches and paintings, was impressive and, without a doubt, the largest one to gather on a single Spanish sailing trip throughout their history.

On his return to Spain Malaspina was sentenced to ten years in prison which served in the Castle of San Antón, in La Coruña... the reason Godoy accused him of conspirator

Of all that knowledge and unsurpassed experience, only 34 nautical cards of Atlas were published. During the Malaspina process in 1795, it had been intended to remove the materials from the expedition, which, however, were preserved in the Hydrography Directorate of the Ministry of Marina in Madrid. The bulk of that work was to remain unpublished until 1885, when the ship lieutenant Pedro de Novo and Colson published his work Political-scientific journey around the world of the discovered and attrevida corbites under the command of the ship captains Mr Alejandro Malaspina and Mr José Bustamante and Guerra from 1789 to 1794 (unfortunately, some materials, such as certain astronomical observations and natural history, had been lost forever). However, part of the collections of natural history collected during the Expedition, especially those related to the Botany, were better fortunate: the herbarium of Luis Née was donated to the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid, where it is currently preserved, and many species were described thanks to these materials by its director, Antonio José Cavanilles.

Until the 20th century history has not been able to appreciate the true magnitude of that company, whose objectives of overcoming the scientific achievements of English and French were fully fulfilled. Only recently have we begun to recognize the value of the information obtained in the expedition of Malaspina, summit of the Spanish Illustration, but it is still dark in history by the travels of Cook, La Perouse and Bougainville, which, as Felipe Fernández-Armeto points out, "continue to have the predominant role in the discourse and imagination of historians."

In recognition of Malaspina's contribution, several Spanish institutions launched a large scientific expedition of circumnavigation that is named after it. The Malaspina expedition (2010- 2011) is an interdisciplinary research project whose main objectives were to study global change and biodiversity in the ocean. From December 2010 to July 2011, more than 250 scientists on board the ocean research ships Hesperides (A-33) and Sarmiento de Gamboa participated in the expedition that brings together scientific research with the training of young researchers and the promotion of marine science and scientific culture in society.

In this link of Spanish TV Radio you can download the 20 videos of the Malaspina Expedition produced by RTVE, which is for its quality an essential and essential document to place this Expedition historically, in the history of world navigation:

http: / / www.rtve.es / alacarta / videos / la-expedition-malaspina /

© 2024 Nautica Digital Europe - www.nauticadigital.eu